Letter from Ingrid Visser and specialists to ambassadors about the ban on Wildlife Imports in China; potential vector Orcinus orca

Experts call on ambassadors to plead the cause of captive orcas in France so that they are not sent in China, because of the presence of coronavirus.

In support of the campaign of One Voice, the biologist Ingrid Visser and a group of experts call on ambassadors to plead the cause of captive orcas in France so that they are not sent there, because of the presence of coronavirus.

The Honourable Lu Shaye

Ambassador

Embassy of the People’s Republic of China

20 Rue Monsieur,

75007 Paris

France

The Honourable Laurent Bili

Ambassador

Embassy of the Republic of France Faguo Zhuhua Dashiguan 60 Tianze Lu

100600 Beijing

People’s Republic of China

The Honourable Cui Tiankai

Ambassador

Embassy of the People’s Republic of China

3505 International Place, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20008

United States of America

The Honourable Terry Branstad Ambassador

Embassy of the United States

No. 55 An Jia Lou Lu

100600 Beijing

People’s Republic of China

Agbeijing@fas.usda.gov office.beijing@trade.gov

Re: Ban on Wildlife Imports in China; potential vector Orcinus orca

Dear Ambassadors,

I am writing on behalf of the undersigned scientists and veterinarians and organisations. We have been carefully following the outbreak of the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV, now designated as SARS-CoV-2), which appears to have originated in Wuhan City, Hubei Province, China. We are aware of the wildlife import ban currently being implemented in China (1), in an attempt to prevent further outbreaks of similar pathogens and we welcome this decision.

This letter focuses on orca (Orcinus orca, also known as killer whales); however, we also wish to draw your attention to the fact that so far two species of cetaceans (whales, dolphins and porpoises) have been identified as carrying coronaviruses. One was identified in a 13-year-old captive-born beluga whale (Delphinapterus leucas) (believed to be born at SeaWorld, USA) and the coronavirus was implicated in the cause of death (COD). This beluga exhibited “generalized pulmonary disease and terminal acute liver failure. … The virus (SW1) was a novel, highly divergent coronavirus most similar overall to group 3 coronaviruses” (2). The authors concluded “… the identification of a previously unrecognized virus in a captive animal underscores the vast diversity of viruses that remains unexplored in animals. These viruses have the potential to be transmitted to humans or other animals, with significant implications for human and animal health.”

Another coronavirus, ‘Cetacean coronavirus’ (also known as CoV (BdCoV) HKU22), was isolated from the faecal samples of three captive Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops aduncus) (held at

Ocean Park, Hong Kong) and the findings of that study indicated that this conroavirus was associated with acute infections and that “viral clearance was associated with a specific adaptive antibody response when the bottlenose dolphins recovered from the infections … none of the three bottlenose dolphins positive for BdCoV HKU22 developed any notable symptoms” (3). The latter is of concern in that dolphins who may appear ‘healthy’ can still be infected with coronavirus.

We are reaching out to you as there have been recent reports regarding the import of five captive orca into China (4) (from France and from the USA), as well as recent attempts to bring wild-caught orca into China from Russia (5).

Orca harbour a range of pathogens. For example, one captive orca held in the USA has been described as having a ‘normal loading’ of pathogens, yet she had more than 40 potentially pathogenic organisms isolated from her tissues, exhalations and excrement. At least four were reported as ‘drug resistant’ and some are also found in humans (6).

Generally, pathogens found in captive orca have not been reported in any detail other than vague descriptions such as ‘bacteria’ or ‘respiratory related’ diseases. For example, an adult male orca captured off the coast of Iceland and subsequently held for decades at SeaWorld (Florida, USA), died in Jan 2019 after years of treatment. He was reported to have had a drug-resistant bacterial respiratory infection (7).

For the past 25 years, facilities holding orca have refused to release necropsy (animal autopsy) reports (8) or simply released vague descriptions of the COD, despite the fact that, among other benefits, necropsy details could provide vital information for identifying zoonotic diseases (i.e., diseases that are transmissible from animals to humans). Scientists and veterinarians believe captive wildlife necropsy information is of great importance (9). Several professionals seeking orca necropsy information have filed a court case in the USA (10) in an attempt to access necropsy reports for several recently deceased animals.

In light of the 2003 outbreak of severe acute respiratory system syndrome (SARS) and the 2012 outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS-CoV) and now the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak – each of which are respiratory diseases in humans believed to be zoonotic – health officials and the authorities should be alert to the potential risks associated with displaying/contact with, not only small wildlife species found at trade markets, but also larger species such as orca used in public entertainment.

To illustrate our concerns, at least 40 captive orca have died from respiratory related diseases and the three most recent orca deaths have been reported as:

- Kasatka (died August 2017, after years of unsuccessful treatment); COD respiratory infection (11) (see attached photographs of this individual);

- Tilikum (died Jan 2019, after years of unsuccessful treatment); COD bacterial respiratory infection;

- Kyara (died July 2017, after living only 3 months); COD lung disease.

In the very few cases where the pathogen that is associated with the respiratory infection is identified publicly, the microorganism was

also known to infect humans:

- Unnamed female orca (died October 2003, captured in Russian waters and survived only 13 days); COD bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa (12) ;

- Haida (died 1982, after 1.5 decades in captivity); COD lung infection from bacteria Staphylococcal sp. (13).;

- Unnamed female orca (died August 1971, after 20 months in captivity); COD salmonellosis (14).

Furthermore, at least two CODs in captive orca have been identified as mosquito-transmitted diseases that have also been recorded in humans (15). Two orca trainers, who have since left the captivity industry, describe the situation eloquently when they write in their peer-reviewed scientific article:

«Although unreported in wild orca populations, mosquito-transmitted diseases have killed at least two captive orcas (Orcinus orca) in U.S. theme parks. St. Louis Encephalitis Virus (SLEV) was implicated in the 1990 death of the male orca Kanduke, held at SeaWorld of Florida. In the second case, West Nile Virus (WNV) killed male orca Taku at SeaWorld of Texas in 2007. Captive environments increase vulnerability to mosquito transmitted diseases in a variety of ways. Unlike their wild counterparts who are rarely stationary, captive orcas typically spend hours each day (mostly at night) floating motionless (logging) during which time biting mosquitoes access their exposed dorsal surfaces. Mosquitoes are attracted to exhaled carbon dioxide, heat and dark surfaces, all of which are present during logging behavior. Further, captive orcas are often housed in geographic locations receiving high ultraviolet radiation, which acts as an immunosuppressant. Unfortunately, many of these facilities offer the animals little shade protection. Additionally, many captive orcas have broken, ground and bored teeth through which bacteria may enter the bloodstream, thus further compromising their ability to fight various pathogens. Given the often compromised health of captive orcas, and given that mosquito-transmitted viral outbreaks are likely to occur in the future, mosquito-transmitted diseases such as SLEV and WNV remain persistent health risks for captive orcas held in the U.S.»

Both SLEV and WNV are diseases to which humans are susceptible and there are no vaccines to prevent, or medications to treat, either virus in people (or animals).

Diseases of concern are not only respiratory in nature, as these two examples show:

- K’yosha (died Jan 1992, after living only 5 months); COD brain infection;

- Haida II (died Aug 2001, after 19 years in captivity); COD brain abscess, fungal infection.

It is already established that orca in captivity are chronically stressed and many, if not all, are immuno-compromised (16). It has been noted that “perfect conditions for new viruses to emerge” develop at the ‘wet’ markets in China where animals are traded and where they are also “massively stressed and immune-compromised” (17).

Seventy percent of zoonotic diseases identified so far come from wildlife (18) and as such these CODs serve as warnings for all forms of wildlife contact and zoonotic diseases. Therefore, our concerns extend to include the orca already in China, not only any potentially imported orca, because these animals are, or will be, on public display in front of large stadium audiences.

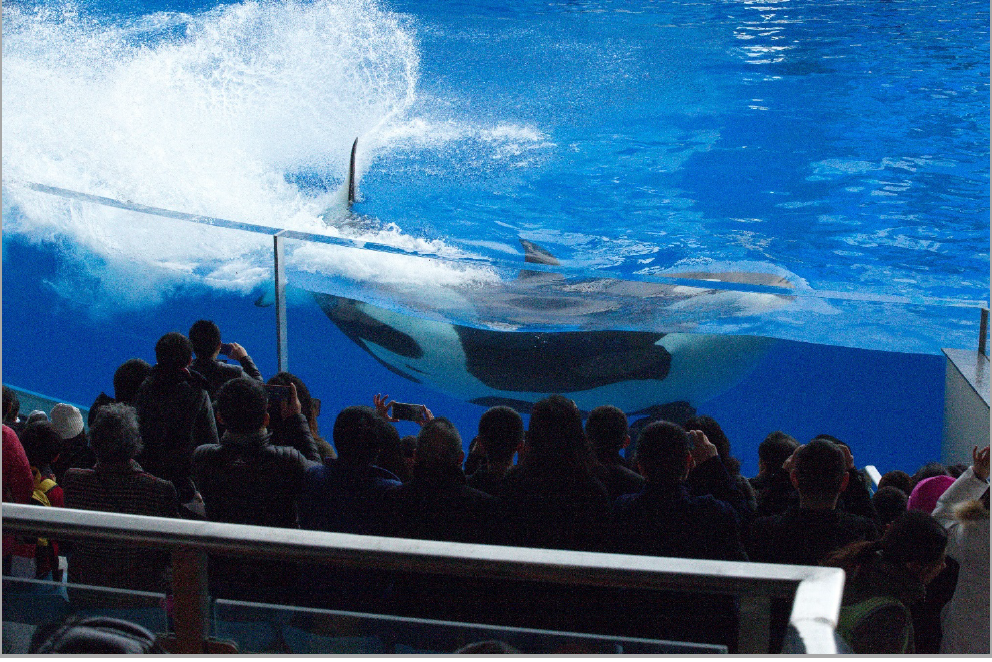

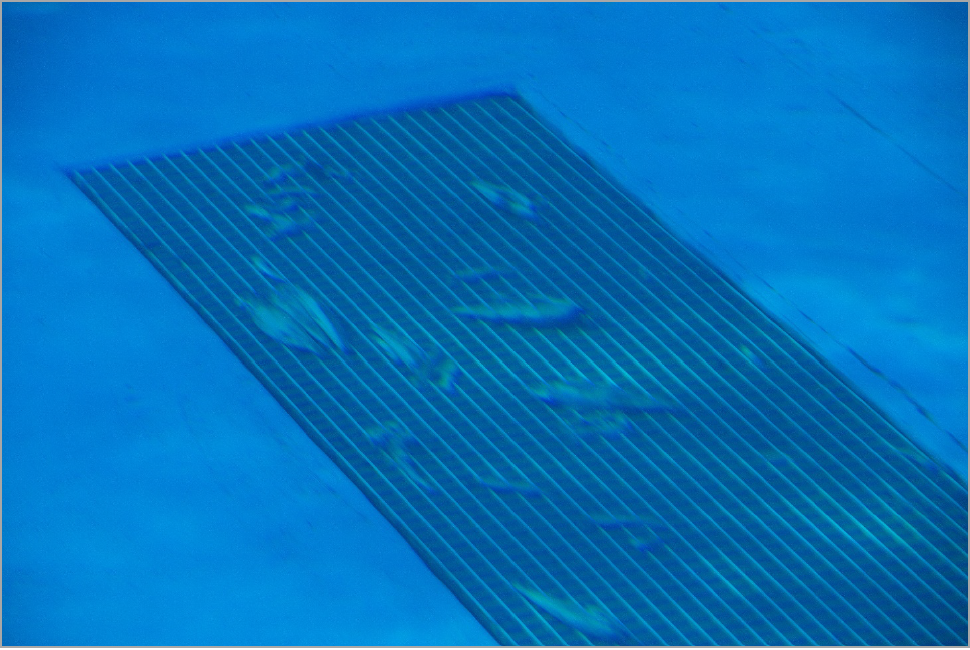

We emphasise that the typical show format (including the existing one in China) includes the orca using their tails to splash the audience with very large volumes of water from the tank (see attached photos from various days and years to illustrate this is a regular occurrence). It should be noted that this is the same water where the orca defecate and urinate and it is the same water that circulates with the ‘off show’ tanks – where in China we have documented dead fish decomposing in the water on the tank floors (see photos attached). Microbes identified in orca faeces have been shown to be resistant to drugs (erythromycin, ampicillin, tetracycline, and chloramphenicol proved to be ineffective against the cultured bacteria) (19). Recently Chinese scientists have found traces of SARS-CoV-2 in the faeces of some human infected patients, possibly indicating an additional mode of transmission (20).

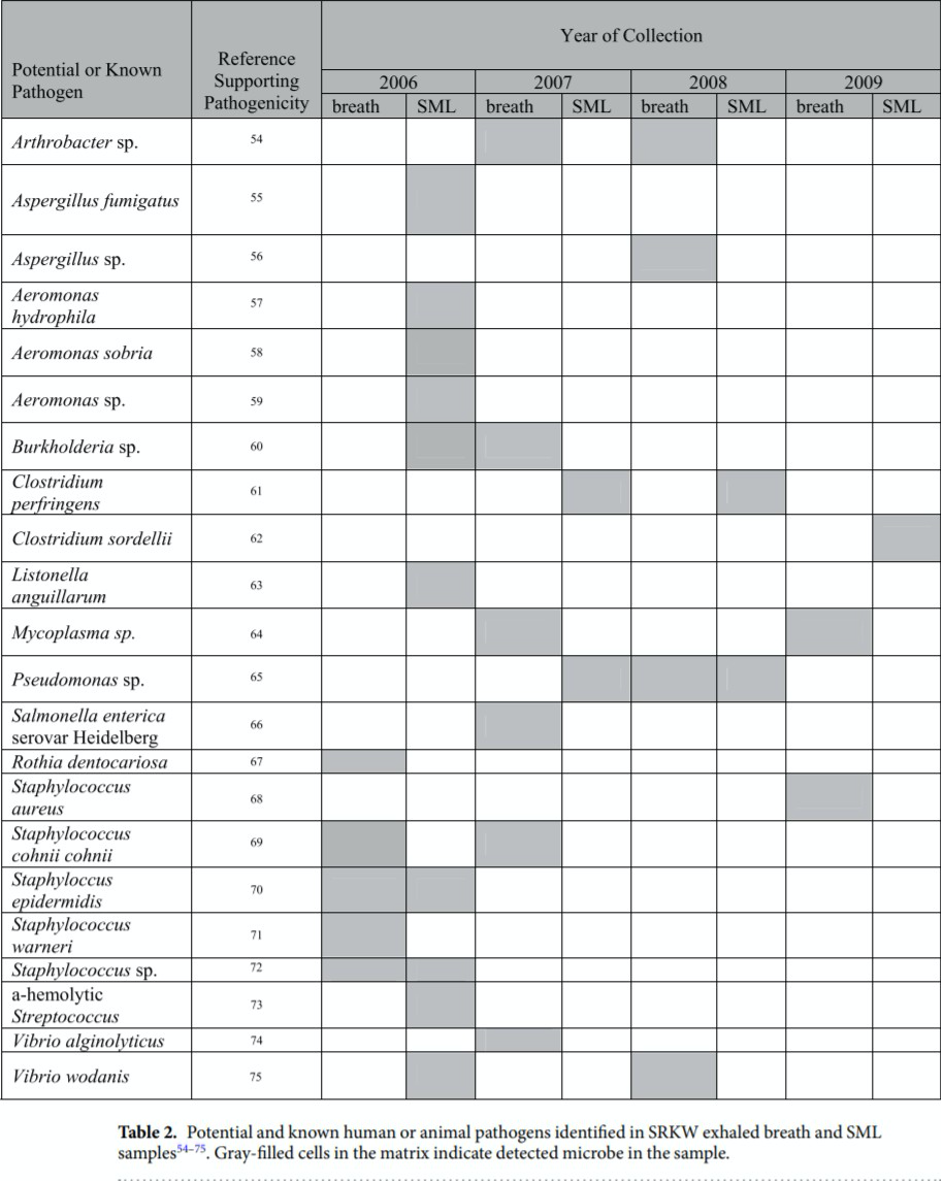

Additionally, orca, particularly after high-energy exercises such as breaching (where the orca ‘jump’ completely out of the water– a trick commonly seen in display shows at theme parks), exhale with force and their breath is known to contain a wide range of pathogens (see the appended Table, where 15 potential and known pathogens were identified from free-ranging orca exhalations) (21).

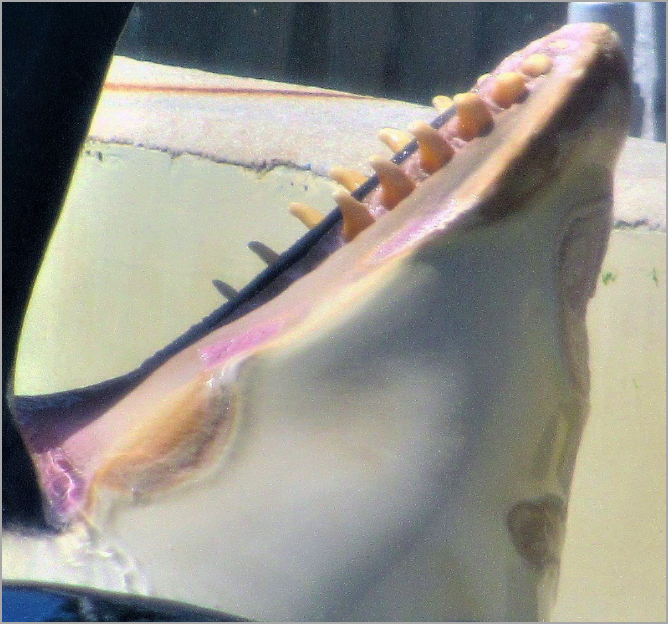

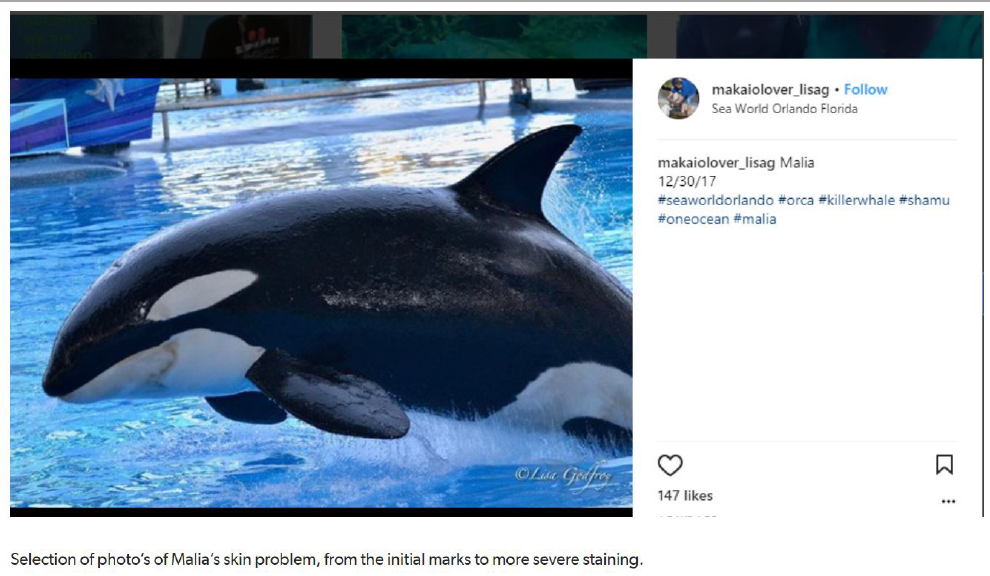

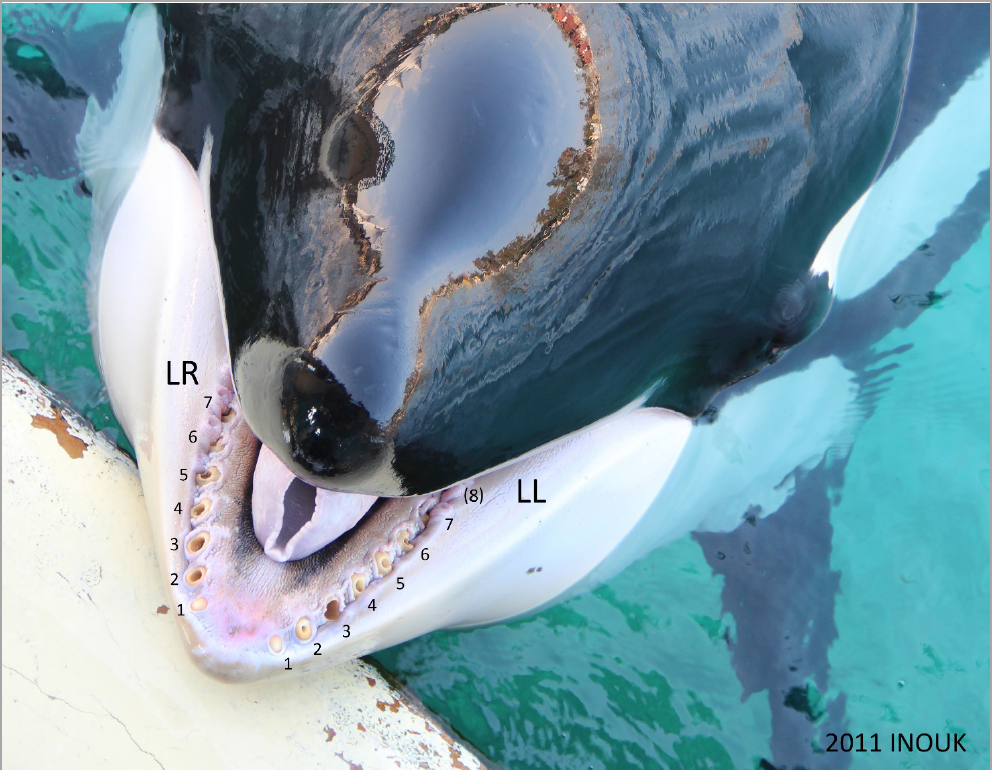

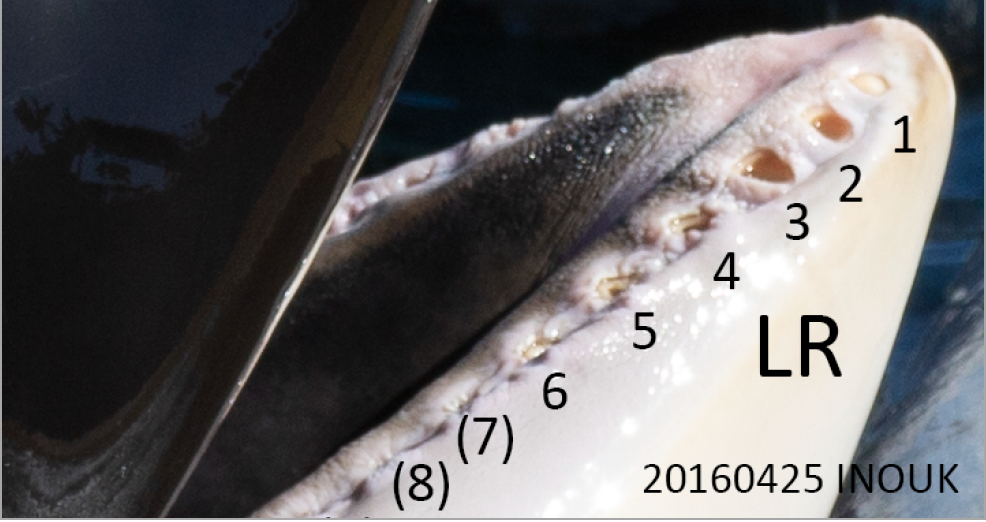

The health hazards for such encounters are already obvious but in addition to these, the orca who are to be imported from France and the USA have severe dental damage (22) (also see appended images), resulting in infections and purulent discharge. Body fluids from these conditions will also enter the water. To further illustrate our concerns, we provide several images (again appended to this letter) from two orca who are held in the USA (one in California and one in Florida), showing some of the issues that manifest themselves in orca, despite “world class veterinary care”.

Given the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak, we believe that the alert levels and quarantine status should be raised for this type of show. We note that Shangdong Province has appropriately implemented a ban on all imports of aquatic animals (including ‘controlling’ breeding). There is a ban on visiting aquariums and these facilities are closed and all exhibitions and activities related to aquatic wildlife have been stopped (23).

China (as of 2019) holds more captive cetaceans than any other country (23% of the world’s captive cetaceans), followed by Japan (16%) (24). Within China there are an estimated 1,000 individual cetaceans from at least 13 species (25). Although we recognise that there has been no recorded zoonotic transmission of coronavirus from cetaceans to humans, there have been examples of transmission from small mammals (e.g., masked palm civets and bats in the case of SARS) (26) and larger mammals (e.g., camels in the case of MERS) (27) to humans. It is well recognised that many species of animals function as ‘reservoirs’ of infectious diseases like coronaviruses and that outbreaks of such diseases are expected to continue in both marine mammals and humans.

Using a precautionary framework, we strongly urge you to pass this information along to the appropriate authorities in China and to request that orca (and other cetaceans) be added to the permanent ban on wildlife imports in China. We also ask that the Shangdong Province implementation of banning shows and closing aquariums is considered as a nation-wide option, with due regard for the provision of adequate welfare of the animals currently held in captivity.

Respectfully,

Ingrid N. Visser, PhD

Cetacean Scientist

Orca Research Trust

New Zealand

On behalf of (listed alphabetically):

Gitte Andersen, DVM

Veterinarian & Owner

Park Animal Hospital Mississauga,

Canada

Monica K. H. Bando, BS MS BVSc PhD

Wildlife Veterinarian

Board, Global Animal Welfare

Maddalena Bearzi, PhD

President

Ocean Conservation Society

USA

Jean-Michel Cousteau Environmentalist/Educator/Film Producer

Founder

Ocean Futures Society

USA

Chris Draper, PhD

Head of Animal Welfare & Captivity

Born Free Foundation

United Kingdom

Silvia Frey, PhD

Marine Conservation Biologist

KYMA Sea Conservation & Research Switzerland

Toni Frohoff, PhD

Wildlife Behavioral Biologist

TerraMar Research

USA

Deborah Giles, PhD

Science and Research Director

Wild Orca

USA

Julie Herbert, DVM,

ABVP Veterinarian (Head of Exotic Animals)

Laval Emergency Animal Hospital, Laval Canada

Sophie Hebert-Saulnier, DVM

Exotic Animal and Wildlife Veterinarian

Avian & Exotic Animal Hospital, Montreal Canada

Erich Hoyt,

Research Fellow

Whale and Dolphin Conservation

United Kingdom

Samuel Hung, PhD

Dolphin Biologist

Hong Kong Dolphin Conservation Society Hong Kong

Mark Jones, BVSc MSc (Stir) MSc (UL) MRCVS, Veterinarian & Head of Policy

Born Free Foundation

United Kingdom

Rob Laidlaw, CBiol and MRSB

Founder & CEO

Zoocheck

Canada

Heather Rally, DVM

Wildlife Veterinarian

Captive Animal Law Enforcement

PETA Foundation,

USA

Naomi A. Rose, PhD

Marine Mammal Scientist

Animal Welfare Institute

USA

Christelle Roy-Corbin, DVM,

MSc Exotic Animal and Wildlife Veterinarian

Avian & Exotic Animal Hospital, Montreal Canada

Jan Schmidt-Burbach, DVM, PhD

Head of Wildlife Research and Animal Welfare World Animal Protection

Germany / Thailand

Thomas I. White, PhD

Ethicist

Oxford Centre for Animal Ethics

United Kingdom

Lindy Weilgart, PhD

Cetacean Biologist

Dalhousie University

Canada

Photo taken 20181217, © Ingrid N. Visser

Photo taken 20181217, © Ingrid N. Visser Photo taken 20181217, © Ingrid N. Visser

Photo taken 20181217, © Ingrid N. Visser

An orca on its side, using its tail to create large splashes which reach the audience, Shanghai Haichang Ocean Park, Shanghai, China

An orca on its side, using its tail to create large splashes which reach the audience, Shanghai Haichang Ocean Park, Shanghai, China (photo taken 20181223, © Ingrid N. Visser).

An orca on its side, using its tail to create large splashes which reach the audience, Shanghai Haichang Ocean Park, Shanghai, China (photo taken 20181223, © Ingrid N. Visser). One of the large splashes reaching the audience, Shanghai Haichang Ocean Park, Shanghai, China (screen grab from video taken 20181223, © Ingrid N. Visser).

One of the large splashes reaching the audience, Shanghai Haichang Ocean Park, Shanghai, China (screen grab from video taken 20181223, © Ingrid N. Visser). Another large splash reaching the audience, Shanghai Haichang Ocean Park, Shanghai, China (screen grab from video taken 20181223, © Ingrid N. Visser).

Another large splash reaching the audience, Shanghai Haichang Ocean Park, Shanghai, China (screen grab from video taken 20181223, © Ingrid N. Visser). Note the umbrellas used to partially deflect the large splash from the orca, Shanghai Haichang Ocean Park, Shanghai, China (photo taken 20190404, © Ingrid N. Visser).

Note the umbrellas used to partially deflect the large splash from the orca, Shanghai Haichang Ocean Park, Shanghai, China (photo taken 20190404, © Ingrid N. Visser). Three children (in white raincoats) in the splash zone created by the orca (also note the umbrellas), Shanghai Haichang Ocean Park, Shanghai, China (photo taken 20190404, © Ingrid N. Visser).

Three children (in white raincoats) in the splash zone created by the orca (also note the umbrellas), Shanghai Haichang Ocean Park, Shanghai, China (photo taken 20190404, © Ingrid N. Visser). Decomposing fish and fish parts on the floor of one of the orca tanks, Shanghai Haichang Ocean Park, Shanghai, China (photo taken 20181217 © Ingrid N. Visser).

Decomposing fish and fish parts on the floor of one of the orca tanks, Shanghai Haichang Ocean Park, Shanghai, China (photo taken 20181217 © Ingrid N. Visser). Decomposing fish and fish parts on the floor of one of the orca tanks, Shanghai Haichang Ocean Park, Shanghai, China. Screen grab from video 20181217 © Ingrid N. Visser

Decomposing fish and fish parts on the floor of one of the orca tanks, Shanghai Haichang Ocean Park, Shanghai, China. Screen grab from video 20181217 © Ingrid N. Visser Decomposing fish and fish parts on the floor of one of the orca tanks, Shanghai Haichang Ocean Park, Shanghai, China. Photo taken 20181218 © Ingrid N. Visser

Decomposing fish and fish parts on the floor of one of the orca tanks, Shanghai Haichang Ocean Park, Shanghai, China. Photo taken 20181218 © Ingrid N. Visser A wild-born female orca known as Kasatka (right) with an undisclosed pathogen creating extensive lesions across her whole body. Of note is that she is held with other orca during this outbreak. Photo circa 20170806 by hunter.d.photography, SeaWorld San Di

A wild-born female orca known as Kasatka (right) with an undisclosed pathogen creating extensive lesions across her whole body. Of note is that she is held with other orca during this outbreak. Photo circa 20170806 by hunter.d.photography, SeaWorld San Di Kasatka, with the pathogen, perhaps at an earlier stage (as date and author unknown), SeaWorld San Diego, California, USA.

Kasatka, with the pathogen, perhaps at an earlier stage (as date and author unknown), SeaWorld San Diego, California, USA. Kasatka (including close-up) with an undisclosed pathogen creating extensive lesions. Photo circa 20170616 by a whistle-blower, SeaWorld San Diego, California, USA.

Kasatka (including close-up) with an undisclosed pathogen creating extensive lesions. Photo circa 20170616 by a whistle-blower, SeaWorld San Diego, California, USA. Kasatka (including close-up) with an undisclosed pathogen creating extensive lesions. Photo circa 20170616 by a whistle-blower, SeaWorld San Diego, California, USA.

Kasatka (including close-up) with an undisclosed pathogen creating extensive lesions. Photo circa 20170616 by a whistle-blower, SeaWorld San Diego, California, USA. Kasatka image posted online 20170808 by ‘seaworldtruthteam’ (note the date the photo was taken is unclear). This posting was 1 week before she was euthanized by SeaWorld who stated that she had an untreatable, drug-resistant pathogen (this pathogen remain

Kasatka image posted online 20170808 by ‘seaworldtruthteam’ (note the date the photo was taken is unclear). This posting was 1 week before she was euthanized by SeaWorld who stated that she had an untreatable, drug-resistant pathogen (this pathogen remain Close-up of Kasatka’s right tail fluke, showing needle ‘track-lines’ as a result of treatment for an undisclosed pathogen. Note the open lesions along the vein lines in the center of the fluke and near the tip. Photo circa 20170616 by a whistle-blower, Se

Close-up of Kasatka’s right tail fluke, showing needle ‘track-lines’ as a result of treatment for an undisclosed pathogen. Note the open lesions along the vein lines in the center of the fluke and near the tip. Photo circa 20170616 by a whistle-blower, Se A female orca (captive born), known as Malia, with an undisclosed pathogen creating extensive skin discolouration and apparently some open lesions. Posted online 20171230 by ‘makaiolover_lisag’, SeaWorld Orlando, Florida, USA.

A female orca (captive born), known as Malia, with an undisclosed pathogen creating extensive skin discolouration and apparently some open lesions. Posted online 20171230 by ‘makaiolover_lisag’, SeaWorld Orlando, Florida, USA. Photographed a week later, this image of Malia shows that the skin discolouration extends onto the chin area and close examination of this image also shows that it is also on her right side. Posted online 20180107 by ‘sworlandophotography’, SeaWorld Orlan

Photographed a week later, this image of Malia shows that the skin discolouration extends onto the chin area and close examination of this image also shows that it is also on her right side. Posted online 20180107 by ‘sworlandophotography’, SeaWorld Orlan Inouk, an adult male orca held in France. This is one of the animals reportedly to be shipped to China. Note that all his teeth are worn down to the gums and they have all been drilled to expose the pulp. Internal documents show that he often has infectio

Inouk, an adult male orca held in France. This is one of the animals reportedly to be shipped to China. Note that all his teeth are worn down to the gums and they have all been drilled to expose the pulp. Internal documents show that he often has infectio Inouk, an adult male orca held in France. This is one of the animals reportedly to be shipped to China. Note that all his teeth are worn down to the gums and they have all been drilled to expose the pulp. Internal documents show that he often has infectio

Inouk, an adult male orca held in France. This is one of the animals reportedly to be shipped to China. Note that all his teeth are worn down to the gums and they have all been drilled to expose the pulp. Internal documents show that he often has infectio Source: Raverty, S. A., Rhodes, L. D., Zabek, E., Eshghi, A., Cameron, C. E., Hanson, M. B. and Schroeder, J. P. (2017). “Respiratory microbiome of endangered Southern Resident killer whales and microbiota of surrounding sea surface microlayer in the East

Source: Raverty, S. A., Rhodes, L. D., Zabek, E., Eshghi, A., Cameron, C. E., Hanson, M. B. and Schroeder, J. P. (2017). “Respiratory microbiome of endangered Southern Resident killer whales and microbiota of surrounding sea surface microlayer in the East

Notes

1. https://web.archive.org/web/20…

2. Mihindukulasuriya, K. A., Wu, G., St. Leger, J., Nordhausen, R. W. and Wang, D. 2008. “Identification of a novel coronavirus from a beluga whale by using a panviral microarray.” Journal of Virology 82: 5084–5088, http://dx.doi.org/10.1128 /JVI.02722-07.

3. Woo, P. C. Y., Lau, S. K. P., Lam, C. S. F., Tsang, A. K. L., Hui, S. W., Fan, R. Y.Y., Martelli, P. and Yuen, K. Y. (2014).

“Discovery of a novel bottlenose dolphin coronavirus reveals a distinct species of marine mammal coronavirus in Gammacoronavirus.” Journal of Virology 88 (2): 1318-1331.

4. https://one-voice.fr/en/news/s…

5. https://www.nationalgeographic…

6. See the Court-released report from Dr Ingrid N. Visser, regarding a captive orca held at Miami Seaquarium, which refers to a number of drug-resistant pathogens (the ‘super bugs’ Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) (Methicillin-resistant

S. aureus), Staphylococcus sp. (CoNS Coagulase-negative) Escherichia coli Sp#2 (Resistant). Case 1:15-cv-22692-UU, Florida Southern District Docket, 2016. Additionally, a number of recent orca deaths at SeaWorld have been linked to drug-resistant pathogens; e.g. see the female orca Unna https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2015/12/unna-killer- whale-died-at-seaworld-san-antonio-this-week/

7. https://www.thedodo.com/seawor…

8. See news article regarding SeaWorld not releasing the necropsy report of the orca who featured in the documentary ‘Blackfish’ https://web.archive.org/web/20…

9. Rally, H. D., Baur, D. C. and McFeeley, M. (2018). “Looking behind the Curtain: Achieving Disclosure of Medical and Scientific Information for Cetaceans in Captivity through Voluntary Compliance and Federal Enforcement.” Animal Law. Lewis & Clark Law School. 24: 303.

10. https://web.archive.org/web/20…

11. https://web.archive.org/save/h…

12. Rozanova, E. I., Alekseev, A. Y., Abramov, A. V., Rassadkin, Y. N. and Shestopalov, A. M. (2007). “Death of the killer whale Orsinus [sic] orca from bacterial pneumonia in 2003.” Russian Journal of Marine Biology 33(5): 321-323.

13. Kielty, J. (2011). Marine Mammal Inventory Report (Deficiencies). St Pete Beach, Florida, USA, The Orca Project Corp (unpublished report, available from https://theorcaproject.wordpress.com/2011/03/18/noaa-nmfs-marine-mammal- inventory-report-deficiencies/), 25 pp.

14. Ridgway, S. H. (1979). “Reported causes of death of captive killer whales (Orcinus orca).” Journal of Wildlife Diseases 15(1): 99-104.

15. Buck, C., Paulino, G. P., Medina, D. J., Hsiung, G. D., Campbell, T. W. and Walsh, M. T. (1993). “Isolation of St. Louis encephalitis virus from a killer whale.” Clinical and Diagnostic Virology 1: 109-112.

Jett, J., Ventre, J., Vail, C. and Dodson, L. (2012). “Evidence of lethal mosquito transmitted viral disease in captive Orcinus orca.” Marine Mammal Health Conference IV. Mote Marine Laboratory and Aquarium, Sarasota, Florida. 5.

Jett, J. and Ventre, J. M. (2012). “Orca (Orcinus orca) captivity and vulnerability to mosquito-transmitted viruses.” Journal of Marine Animals and Their Ecology 5(2): 9-16.

St. Leger, J., Wu, G., Anderson, M., Dalton, L., Nilson, E. and Wang, D. (2011). “West Nile Virus infection in killer whale, Texas, USA, 2007.” Emerging Infectious Diseases 17(8): 1531-1533

16. Marino, L., Rose, N. A., Visser, I. N., Rally, H. D., Ferdowsian, H. R. and Slootsky, V. (2019). “The harmful effects of captivity and chronic stress on the well-being of orcas (Orcinus orca).” Journal of Veterinary Behavior https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jveb.2019.05.005.

17. https://web.archive.org/web/20…

18. https://ghss.georgetown.edu/ih…

19. Potter, S. L. (2013). “Antimicrobial resistance in Orcinus orca scat: Using marine sentinels as indicators of pharmaceutical pollution in the Salish Sea.” Master’s Thesis, p. 125, Evergreen State College.

20. https://www.scmp.com/news/china/politics/article/3048611/coronavirus-scientists-identify-possible-new-mode- transmission

21. Raverty, S. A., Rhodes, L. D., Zabek, E., Eshghi, A., Cameron, C. E., Hanson, M. B. and Schroeder, J. P. (2017). “Respiratory microbiome of endangered Southern Resident killer whales and microbiota of surrounding sea surface microlayer in the Eastern North Pacific.” Scientific Reports 394: 1-12.

22. Visser, I. N., Jett, J., and Ventre, J. (2019). INOUK – Captive 20-year-old male orca, with chronic and extensive tooth damage. Report prepared for One Voice (www.one-voice.fr), March 2019, 25 pp.

23. https://web.archive.org/web/20…

24. https://www.worldanimalprotect…

25. http://chinacetaceanalliance.o…