Animal testing: what do we choose when we are being lied to?

On 28 April, a few days after World Day for Animals in Laboratories, the UFC-Que Choisir Association published a ‘decoding’ of animal testing entitled “Things are moving in labs [Ça bouge dans les labos]”. But between unacceptable estimations and a very conspicuous complacency towards laboratories, the copy needs to be reviewed. We are reviewing it.

“We could not stop naming situations where this model is irreplaceable.” While the article started fairly well with the interview of a researcher who works on organoids to carry out advanced biomedical research, the ‘decoding’ by UFC-Que Choisir quickly shows its limits. No mention of the capturing of primates abroad to feed the farms that supply French laboratories, nor of the general obscurity of the civil service on these issues. However, One Voice was contacted for this article and provided responses and precise data and sources.

Always the same old tune

While the general public do not generally know what the ‘3 Rs’[1] are, those who defend animal testing have succeeded in imposing their views on journalists and even in the regulations, which nowadays they boast as being based on this ‘ethical’ principle that consists of using the least animals possible, in the best possible conditions, and only while there is no alternative.

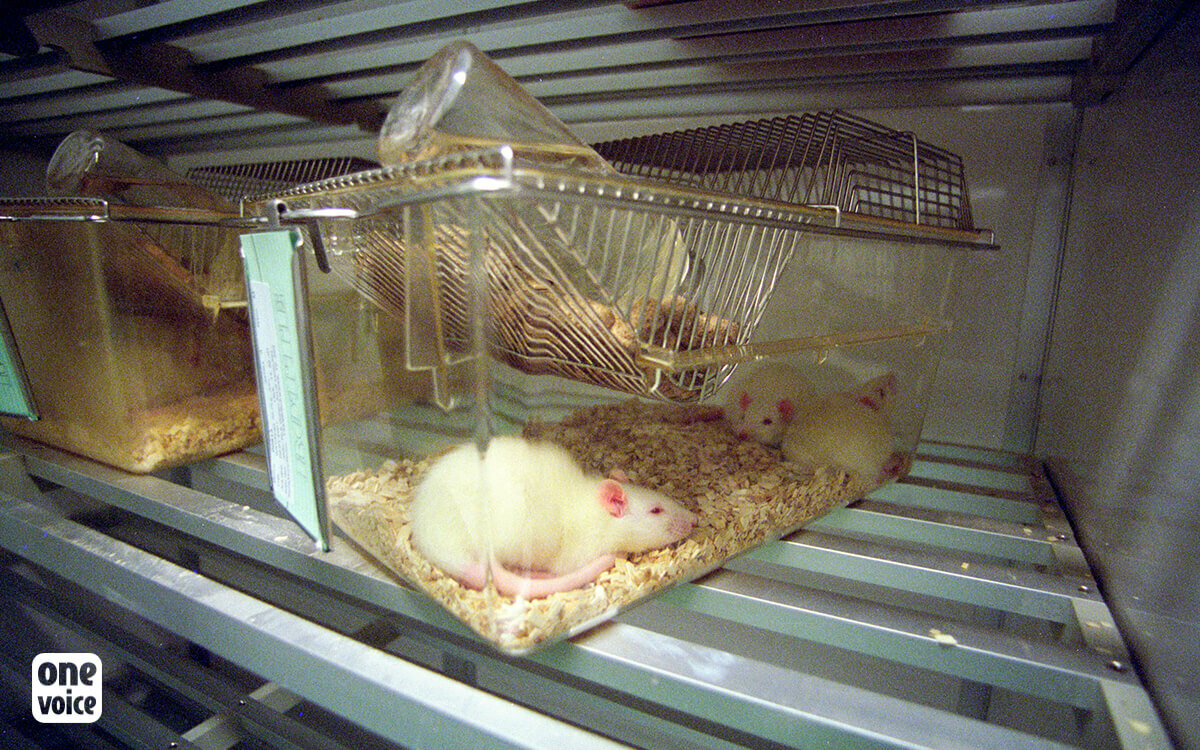

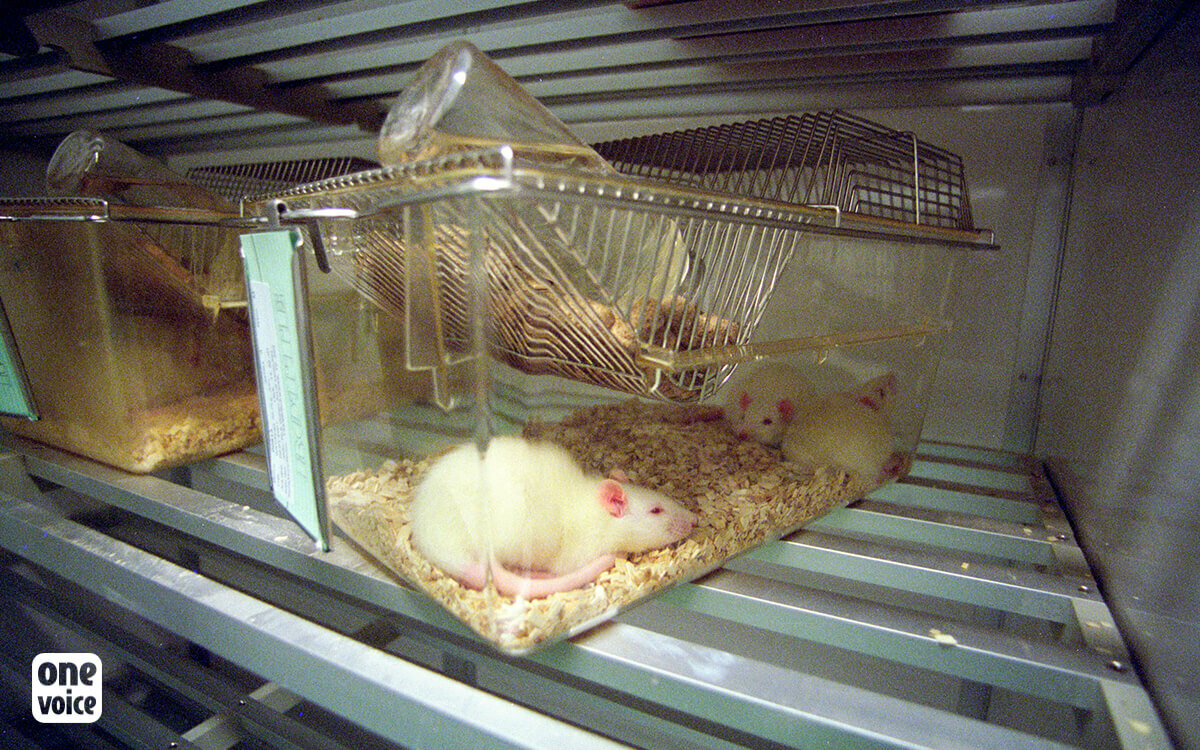

However, it is sufficient to look at the progression of the figures over the last few years to observe that the ‘reduction’ is hardly convincing. And we gave a forced laugh when UFC-Que Choisir said that they had seen rodents at the Institute of Psychiatry and Neuroscience of Paris “as well cared for as possible”, specifying that there was cotton and wood in their cages and the fact that “the law sets the rules” on the dimensions of these cages. If they were interested in the details of these regulations, they could perhaps explain to the public how a plastic box that is hardly bigger than an A4 sheet, caging up to four rats who spend their life in there, constitutes treatment that is as good as possible for these animals.

But no, “only the killing practices make them cringe” — not because they would be harmful to the animals as individuals (why would being killed bother them, after all?), but because it is “unlikely to be insignificant for the person that does it”. Still as always, humans come before other animals. We can imagine that if the journalist had been able to see the killings using gas, it would have seemed trivial to him as well.

The limits of ‘Replacement’

When it comes to ‘Replacement’ with non-animal methods, mentioned at the beginning of the article in relation to organoids[2], we can actually be glad for small advances and recommend (as UFC-Que Choisir have) “a significant budget given to replacement methods”. But the underlying problem remains, which reveals the hypocrisy of the 3Rs when they help to justify words such as ‘irreplaceable’ or ‘necessary’.

In fact, if we cannot find the same results with another method, Replacement will go down the drain. No one is responsible for evaluating the possibility of redirecting money intended for this research towards prevention campaigns, epidemiological or clinical[3] research, better reimbursements for known treatments, or socio-economic support for people at risk.

Without pretending that it is possible to model using a computer or in cell cultures of behavioural or complex cognitive problems, we can ask what is looking to be replaced: do we want to know what motivates rats to inject themselves with doses of cocaine, or do we want to try to understand and help people suffering from addiction? Do we want to see how rodents recognise their fellow rodents in different situations, or do we want to help people with degenerative memory disorders?

Unfortunately, if money has been set aside for experimental research, then it will remain in experimental research, even if it would be better spent elsewhere.

Why are there so many errors in the media?

Even beyond these technical or ethical aspects and the implicit contempt for the animals’ interests, it is difficult to understand how the media continues to repeat errors that we have explained long ago.

When the Ministry of Agriculture themselves published lies on their website concerning the results of inspection, we can better understand the problem and we have to restore the truth again: no, the inspections by veterinary services did not lead “in more than 80% of cases to a glowing result”. Quite simply because the establishments that achieved A and B grades during inspections most of the time displayed at least a few minor or mid-level non-conformities, of which some were to be penalised according to article R. 215-10 of the Environmental Code.

In other cases, it is the journalists who show complacency towards public services that are difficult to understand: how can one explain in this article by UFC-Que Choisir the proportion of unexpected inspections in 2019 in France (25%) in comparison to the European average from 2013 to 2017 (40%), a period during which France went from 6 to 17% of unexpected inspections?

Finally, the subjects are sometimes too complex, or the information too hidden to be found without specifically asking the specialists for it. When UFC-Que Choisir claimed that it is “unknown” whether the European Chemicals Agency’s requirement for testing cosmetic ingredients on animals “remains to be the exception”, it was in fact the journalist who was unaware that an article published in 2021 had already answered this question. Out of the 419 exclusively cosmetic ingredients registered by this agency, 63 were involved in live animal testing since the bans in 2009 and 2013. And let’s not forget the thousands of multi-use ingredients that are tested in other settings, or international marketing, which largely justify the existence of ‘cruelty free’ certifications and the “Save Cruelty Free Cosmetics” European Citizens’ Initiative (which we invite you to sign to reach one million signatures between now and August).

The beginning of a solution…

We already know: animal testing still receives far too superficial a treatment in the media, who reiterate each others’ statements without ever giving space to in-depth discussions on specific points.

We must recognise that even in consulting different sides of a discussion, even by trying to assemble as much information as possible and cross-referencing sources, writing an article that is a few paragraphs long without losing the substance of the discussion nor risking misinterpretation is a difficult task. And once again, although One Voice has been questioned for the UFC-Que Choisir article, clearly that is not enough.

We imagine that the articles being proofread by the various people questioned would allow them to verify that the most important elements have been well-understood and taken into account. This would also give the possibility for each of these people to respond to the remarks and ideas of others. This would be a much longer and more difficult task, but we could logically think that the result would be much better, that many biases would be avoided, and that the public would be better informed.

If you would like to look deeper into the subject of animal testing or set up discussions, do not hesitate to contact us.

[1] “Replacement” (with methods that do not use animals), “Reduce” (the number of animals used, thanks in particular to statistical methods), “Refine” (the conditions the animals are kept in by giving them something to keep them occupied, and experimental procedures using analgesics and less invasive methods).

[2] Organoids are miniature models of human organs made thanks to three-dimensional cell cultures to reproduce the functions of the organs, making it one of the most prolific ways to replace animal testing.

[3] Epidemiology is a basic tool in public health research which consists of studying the distribution of health problems in the population and using statistical modelling to better understand how to find preventative or curative solutions to these problems. Clinical research brings together scientific studies involving volunteer human beings, having given their free and clear consent for supervised research under bioethics rules, specifically guaranteeing respect for the integrity of each person.

Translated from the French by Joely Justice