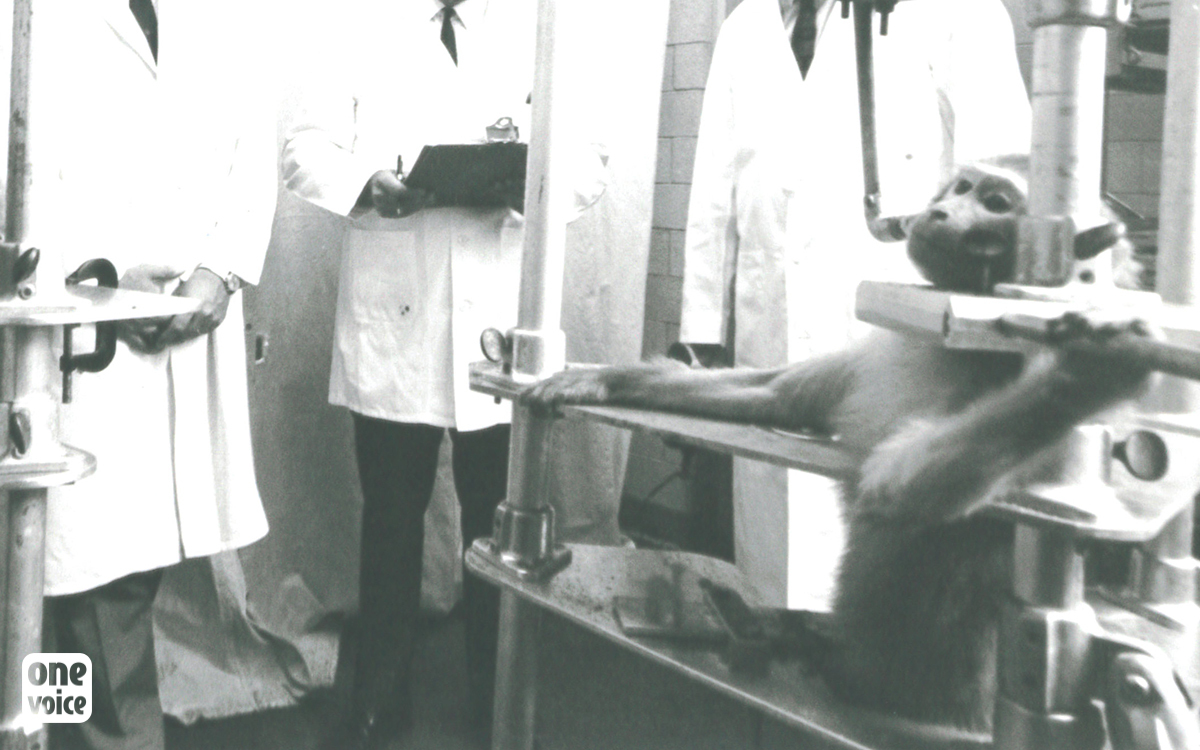

Will there soon be more primates in laboratories?

Last June, during the International FELASA Congress 2022, we felt that the restrictions on the use of primates for experimentation were not to everyone’s taste.

While China has not exported monkeys to laboratories for two years, Air France predicts the end of them being transported to be any moment now and the European Union is ready to ban the use of primates born to parents that have been captured in the wild. Changes that are not to everyone’s taste…

Friday 18 June in Marseille. The international FELASA Congress 2022 has finished and it leaves us with a bitter taste in our mouths. Among the latest responses to the congress, the President of the European lobby on animal testing made a point of talking about the threat weighing on the use of primates for laboratories. A bad thing according to him.

First generation primates in captivity soon to be banned

In fact, the use of new primates from the first generation born in captivity (‘F1’, meaning those whose parents were captured in the wild) will theoretically be banned from November 2022, according to a report by the European Commission from 2017 following a feasibility study.

At the congress the reactions were mixed at best. After all, “what is the difference between F1 and F2+, since they are all born in captivity and have never known anything else?”. As if this justifies anything… And “if the regulations were concerned by captures and wanted to discourage them through these measures, they should have specified”! Which they do, explicitly, since we read in the report from the European Commission that these measures aim to “put an end to the capture of non-human primates in the wild for scientific and breeding purposes”.

Lastly, it should not be necessary for researchers who are very concerned by the ‘welfare’ of ‘their’ animals to export to China, where the conditions are “deplorable”, if the European Union starts to over-limit their source of supply or pose overly strict limits on what they can inflict on primates. Is the concern for this ‘animal welfare’ therefore only valid if the local regulations require it?

We talked about ethical short-sightedness in the previous bill, but here it reaches a completely different level and it would be hard to believe that it is not voluntarily maintained by the industry.

The problem with capturing

We even heard from a researcher that the difficulties with cohabitation could justify individuals being captured by breeding farms who supply laboratories. Still a rhetorical fallacy for which the reasoning is contradicted by a recent webinar organised by the Asia for Animals coalition (which One Voice is part of).

It is true that cohabitation between the human population and primates is sometimes difficult – which implies safety issues to humans, and mistreatment and regular violent trafficking for non-human primates (macaques in particular). But specialists on this subject emphasise that it is the education of human populations on waste management and sharing spaces with other species that is vital in resolving cohabitation conflicts, alongside neutering campaigns aimed at female macaques.

Capturing has never resolved anything and has even created a new problem: despite localised growths, long-tailed macaques are threatened with extinction on a global scale nowadays. Since the 2000s, a report by CITES has mentioned the risk represented by capturing for these macaque populations. And they were not wrong: this species was classified as ‘vulnerable’ in 2020, then ‘endangered’ in 2022 on the IUCN Red List.

A classification which echoes the ban on exportations of primates from China since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, but also the recent decision by Air France to soon stop transporting primates to laboratories.

The media battle

Faced with this combination of factors which could speed up the end of the use of primates in experimentation, the media is dealing with two sides of the story.

On one side, those who defend animal testing structure themselves at the centre of their inter-professional organisations to convince the public and politics that the use of primates is absolutely indispensable in the discovery of new treatments – setting aside the epistemological hindsight that should be standard in all scientific research work.

On the other, the associations and people who want to see the end of animal testing try their best to have a say in the matter, through platforms or letters addressed to the media to condemn the one-sided treatment of the subject.

Journalistic work is very complex. But democratic work is even more complex when public establishments and private companies come together to defend practices criticised by the public that are based on a fundamental injustice.

We invite journalists to contact us to balance the debates on the basis of sourced information that is sometimes difficult to access.

This article is the last in a series which will present different aspects of the FELASA 2022 congress:

- Transparency and communication strategies in animal testing

- Language elements and rhetorical fallacies in animal testing

- The animal testing industry makes propagand

- The ethical short-sightedness of animal testing

- Will there soon be more primates in laboratories?

Translated from the French by Joely Justice